This series, ‘Beyond The Matildas,’ takes us back through the history of Australia’s most-loved sporting team. It delves into the memories and experiences of its pioneers, and sheds light on the many aspects of life for Australia’s women footballers—both during and after their playing careers—that we don’t hear much about. ‘Beyond The Matildas’ celebrates the achievements of several generations of women players, while also looking at the more complex aspects of football for Australian women over time—the emotional struggles of losses and injuries, balancing football with other careers, the bumpy transitions into retirement, the new lives they forge, and the legacies they leave behind.

Adelaide—South Australia

Family dynasties are rare in football—rarer still in Australian football.

But if you were to wander down to Port Adelaide Pirates Soccer Club one bright, cool Sunday morning in May and chat to the volunteers sitting at the canteen or setting up the nets, there is one name that you’ll hear again and again. A name that has cemented itself as one of the great family dynasties in Australian football. Alagich.

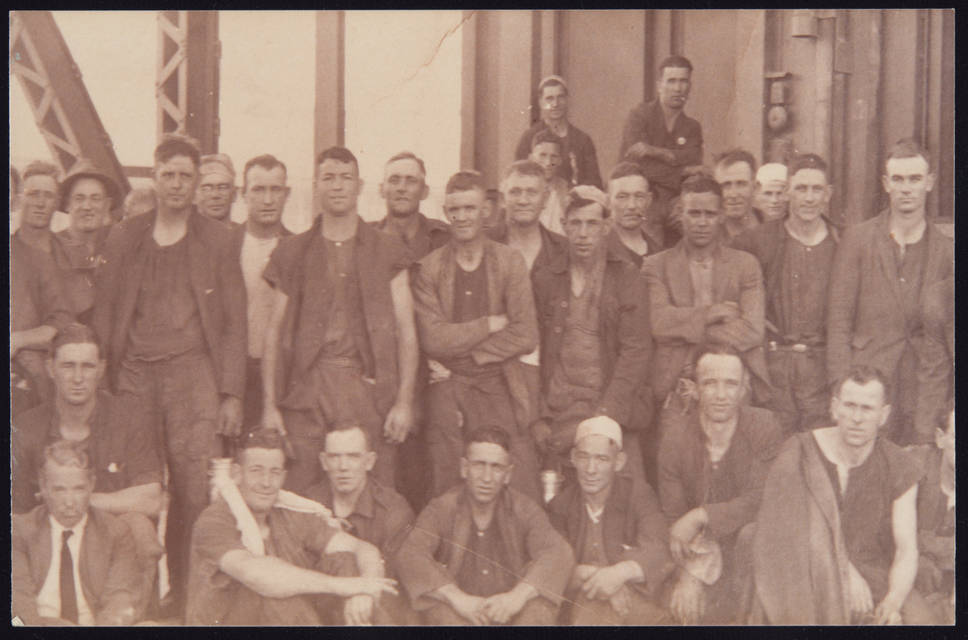

It started with Marin. Marin was a boxer and amateur footballer who, alongside his two brothers Rudolph and Slavko, founded the Broken Hill Soccer Association in 1938. Like his father Josip, a Croatian-born migrant who worked in the mines in the far west of New South Wales in the 1920s, Marin was heavily involved in trade unionism. After spending time in the army and in defence factories during the Second World War, Marin later trained as a teacher.

The war saw thousands of migrants from Europe arrive on Australia’s shores throughout the 1940s. Marin soon recognised the poison of racism being directed towards new migrants and refugees, and the damage it was causing to families like his own. But Marin was kind. He was not one to give up on people. He recognised the power of sport—and of football in particular—as an antidote to hatred and bigotry; a space where differences could be set aside, worked through, or forgotten altogether. Marin helped form the Sydney Yugoslav Soccer Club in 1946, the first of its kind in the area. He also played a part in establishing several other local clubs including the now-defunct Yugal Ryde, which became a powerhouse of New South Wales football in the 1960s and 1970s.

Marin’s son, Joe Alagich, was one of the stars of Yugal in its prime, playing over 260 games for the club across 16 years. Joe was also the first Alagich to represent Australia after being selected for the Socceroos in 1969. He took part in Australia’s bid to qualify for the 1970 World Cup in Mexico alongside the likes of Johnny Warren, a man whose name is now emblazoned on the medal given to the best player in the modern-day A-League competition.

Marin’s brother Slavko (or “Len”) also had a son: Colin. Following in his father’s footsteps, Colin Alagich made his own mark on South Australian football, playing over 300 games and officiating for the Port Adelaide Pirates for decades. He wrote the first-ever history of football in the area, titled 100 Years of the World Game in Port Adelaide, with an updated version—115 Years of the World Game in Port Adelaide—published last year. The impact that Colin had on football in Adelaide was unparalleled. In early April 2019, the club reported that Colin had passed away. The social media messages from people who knew Colin, expressing sadness and gratitude for his passion and guidance at Port Adelaide, numbered in the hundreds.

This is the point in the Alagich family dynasty where two paths diverge.

Colin had five children: Richie, Kerry, Chris, Dianne, and Colin Jnr.

Richie Alagich played over 250 games across his professional career in Australia’s National Soccer League, representing West Adelaide, South Melbourne, and Brisbane Strikers. He was awarded Players’ Player in his first season representing Adelaide United in the A-League in 2003, reaching the final of the Asian Champions League with the Reds in 2008. Richie also represented Australia at Youth and Olympic level.

Growing up within this footballing family made it almost inevitable that Dianne Alagich would play the game. It was as though her future was pre-written, woven into the history of her family name.

“I grew up with four brothers, so they sort of forced [football] upon me. As soon as I could walk, I had a ball at my feet. I didn’t really know any different from there. I always had someone to play with in the backyard,” Dianne said of her first memories playing football.

“I played at my local primary school, then went and played at Port Adelaide. All my brothers played at the same club.

“I’ve been pretty lucky with my family. My older brother Richie played professionally, so I always got along really well with him and was able to bounce ideas off him. That’s how our relationship grew; we grew together playing football.”

Dianne entered the national team ranks at a young age, being picked for the under-16s Australian team when she was just 13 years old. The team would meet only once a year, at the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra. When she was 16, Dianne was promoted to the Matildas’ senior squad.

Having grown up surrounded by the Alagich clan, Dianne found herself, all of a sudden, on her own—forging her own path into the senior national team, and building her identity as the first female Alagich to pursue football professionally.

“It was pretty intimidating, actually. The sort of characters who’d been around for quite a while; it probably wasn’t the most welcoming environment.

“I found it quite a challenging environment coming into it, being so young and coming into an environment that had been quite established; some of those players had been part of the national team for quite some time. And I came into the team when they’d just missed out on the World Cup [Australia were knocked out in the group stage of the 1995 World Cup in Sweden], so there were some new players coming in as well. It was a pretty tough environment.”

However, there was one player that Dianne remembers with warmth and gratitude for making her feel at home—for welcoming her to her new Matildas family.

“I still remember Julie Murray. I knew who Julie Murray was because she had been an assistant coach for the under-16s Australian team. She welcomed me with open arms and I’ll never forget that actually because not all the Matildas were at that point. I still remember Julie welcoming me and pretty much offering that support to me because I was so young.

“They’re not going to know who you are as a person, really, and you just sort of come in with starry eyes. So it was a combination of me being so young and feeling that intimidation, especially being from Adelaide when there was no one else in the team from Adelaide.

“I felt like a really small fish in a big bowl.”

Despite playing for the Matildas for over a decade including three successive World Cups, spending three years in the USA’s top women’s league, and captaining Adelaide United in their first W-League season, Dianne’s career differed from that of her brother in a key way: financial support.

While Richie was earning a living playing in the inaugural A-League season with Adelaide United, Dianne struggled to make ends meet through her work as a footballer. Not only did she not get paid enough to play football itself, but it was also difficult to find jobs that allowed her to travel as much as she needed to.

“I found it extremely difficult when I had to be financially independent. It was very, very hard to get a job where they were okay with me going away so much with football. I just had casual jobs and never focused on my career, unfortunately. I had my blinkers on, and I knew what I wanted to achieve with football, so that’s what I did.”

This lack of financial support came to a head for Dianne in late 2003 when the United States’ Women’s United Soccer Association (WUSA), the first women’s league in the world to pay their players professional wages, folded. Dianne suddenly found herself out of work, and with little work experience.

“I’d been playing professionally in America for three years, and then the league folded, so in 2004 I returned to Australia without anything, basically. Without a job.

“But I think the skills we gain as professional athletes… they give us life skills. I actually applied for the firies and applied for a customs position; I wanted a customs position and to move so I could start a career. And that coincided with wanting to move my football as well.”

By the time Dianne retired in 2009, she had already been employed full-time in the public service for four years; such was the lack of financial support for Australia’s women footballers barely a decade ago. It’s an important part of the history of the sport that is easy to forget these days as the current Matildas earn a year-round wage playing football. Chronic knee injuries also meant that Dianne knew retirement was on the horizon at a much earlier stage than many others do.

“I got that full-time job because I knew I needed to and I didn’t want to just have football, especially because I had so many injuries, so I knew I needed other avenues.

“I needed to support myself. I had a mortgage. So, for me, having a full-time job was very important, for my financial freedom.”

While her financial livelihood was precarious, there was one thing that remained constant throughout Dianne’s career and into her retirement: her family.

“My family were everything to me. Every time I didn’t make a team or we lost a game or I got an injury, I’d call my dad up or my brother or my mum and have a chat to them, and they’d give me that sense of ‘you’re more than just football, you’ve overcome this or that’. You can have your blinkers on during your career and not focus on anything else, and you sort of realise that there’s a bigger picture. There’s more to life.

“They’re always there for me no matter what. And I knew that; they’re always gonna be there for me, when you’re doing well, when you’re not, when you’ve made a mistake… in life, I mean.”

Although she was financially secure in her new career, the understanding of herself that she had developed as a footballer—and as the latest success story in the Alagich family dynasty—was something she struggled to re-shape when she hung up the boots.

“What I didn’t cope well with was missing the game and having your sense of identity related to your team [gone],” she said.

“It’s still hard now. You don’t get that emotional high in life that you used to get playing football. But it’s like everything; you find ways to deal with it.

“I didn’t struggle in the sense of not having a routine [anymore], but it was a big black hole when I retired and I set myself up the best way I knew how. But you still lack the biggest part of your life… your passion in life is gone. It’s hard to get through that. It’s a personal struggle and everyone comes out of it the best way they can.

“It’s hard to switch off from what you were.”

While the Alagich men were able to transition rather easily into retirement while still being involved in football—becoming coaches, administrators, or officials—this was an example that was not so easy for Dianne to follow.

“For me, coaching was nowhere near the same as playing. You try to replace [that feeling] but you can’t really replace something that’s not the same and that you don’t have the passion for,” she said.

“I definitely had opportunities to coach—I went to the 2010 Asian Cup as an assistant coach—but for me, it was too close to when I was playing. I really needed to distance myself from the game and give myself some time to heal in some respects. Even now, there’s not many paid positions [in coaching], and to go back to not getting paid to be involved in football is something that I’m not prepared to do.

“For my generation of Matildas, we gave up so much financially.

“You feel you’re a pioneer in the fact that over the last couple of years, we finally got some sort of payment and contracts, and then you retire and you start the process of coaching where you’re doing it for free [all over again].”

While she has not followed the path of the Alagich men in pursuing coaching as a career, she nonetheless volunteers as a coach on weekends and is also working to set up a Pararoos Development Centre to support a women’s team.

“I feel like I’ve got this burning thing in my chest to try and achieve something, and you kind of have to hold it down [or] put it into different areas.”

While Dianne has represented the Alagich family name at the highest levels of professional football, the history of the Alagich family continues to be written, as Dianne is also a mother.

“My most important job now is my children and being a good mother for them.

“Some people ask me about my daughter, ‘oh, is she going to be a Matilda?’ and I’m like ‘I really don’t care, I just want her to be happy and healthy.’ For her to be happy is my life goal now. What you consider important is very, very different once you have children.”

Pregnancy and motherhood have been significant processes for Dianne; not only in producing the next generation of Alagichs, but also in re-shaping her own identity and relationship with her body; things that had become fractured during and after her playing days.

Elite sport is an industry where the much of an athlete’s success rests upon their body being in peak physical condition. The constant monitoring and testing of their bodies within this environment can sometimes warp how athletes—particularly young women who are already pressured by society to look a certain way—see and understand themselves. While she was playing in the United States, Dianne recalls one of her coaches making a comment about her weight.

“[That’s] when it started. That was enough for me to be very self-conscious and probably not eat properly and increase my workload, changing what I could in order to lose weight. And that really impacted on my injuries, as well. It was a spiralling effect at that point,” she said.

“After retirement, I found I tried to control my body in an unhealthy way. I put more emphasis on having to look the right way, which was harder because I wasn’t training as much… To not always wake up and go ‘okay, I need to do this session and that session’… it was unnatural to wake up and not train.”

Dianne credits seeking professional help with allowing her to develop a healthier relationship with her body and her sense of self after the high-monitoring, high-pressure environment of professional sport.

However, it was pregnancy that fundamentally changed how she saw and understood herself.

“Having children made me so much more aware of my body in that my body is something I need to look after. It can produce a child. It’s the most amazing thing.

“For me, it was almost a forced therapy. I wanted to do everything I could to have a healthy child…. It was a really good healing process for me, actually.

“When you have the baby and you’re a few kilograms over what you think is the correct weight, then you get this little baby… you forget all of that. You almost don’t have time to think about yourself anymore, so those thoughts… all I thought about was this baby and how I can make it healthy. It was a really nice process to go through.

“You still have that voice I guess, but the voice is quieter. It’s been amazing to go through all that. You realise that all your successes in life… nothing compares to having a child.”

The story of Dianne Alagich is different to that of her forefathers. While her famous surname has become a moniker for mid-century multiculturalism in Australia and the role football can play in bringing communities together, her identity as the first female Alagich to pursue football professionally means she has added an extra dimension to her family’s legacy.

Like Marin, Dianne’s experience reflects the commitment and the sacrifices of those who aspired to overcome the adversity of a culture that had never included them. Hers is a name that encapsulates the history of football in Australia, signalling both the introduction of the migrant communities who helped popularise the game throughout the mid-twentieth century, as well as the more recent acceptance and increased support of women wanting to make a living playing football.

Dianne’s story is one of both struggle and triumph; of representing a nation and a name on the world stage, of laying the foundations for the women who would break new ground in professional women’s football, and of adding new pages to the history of the Alagich family dynasty—with some blank space left for the Alagichs yet to come.