Last week, Sports Illustrated Swimsuit announced that US women’s national team superstar Alex Morgan would be the cover model for their 2019 edition. The cover and accompanying photo set sent most of the women’s football community into raptures, alongside the news that three other USA footballers—Megan Rapinoe, Crystal Dunn, and Abby Dahlkemper—also had their own photoshoots in the same edition.

BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE! @alexmorgan13 lands the final cover of #SISwim 2019! ⭐https://t.co/4kN0K8kDOt pic.twitter.com/xdlGQaebKY

— Sports Illustrated Swimsuit (@SI_Swimsuit) May 8, 2019

The article accompanying the announcement begins with the sub-heading: “When it comes to women’s equality, the members of the USWNT aren’t just talking about change, they’re creating it.” The article itself opens with a discussion of USA football legend Brandi Chastain, whose successful penalty kick against China won them their second FIFA Women’s World Cup title in 1999. The author goes on to describe the now-iconic image of Chastain who, after scoring the winning penalty, ripped off her jersey and waved it around her head before falling to her knees in celebration.

In starting the article in this way, the author draws a deliberate parallel between the image of Chastain and the images of the four footballers in Sports Illustrated Swimsuit; a parallel that highlights the idea of women athlete’s semi-nude bodies as a symbol of empowerment. However, it doesn’t take an art critic to see that Chastain’s photo and, for example, the photo of Alex Morgan that graces the 2019 cover, are not the same.

Chastain’s photo has become so iconic because her presentation of her semi-nude body was decidedly not sexual. Rather, the sexualisation of the photo came afterwards, when the mainstream media (which, at the time, was controlled almost entirely by men) picked it up and attributed outdated sexual and moral codes to Chastain’s behaviour. But the photo itself does not suggest as such. In fact, Chastain’s semi-nude body, clothed in a plain black sports bra and long white football shorts, is not the primary point of interest here. Instead, what we focus on in the image—what our eyes are drawn to—is Chastain’s face. Her eyes are closed as she lets out a mighty roar, her team-mates rushing over to her in celebration as the enormous crowd shimmers behind them.

The visual language of Morgan’s photo, on the other hand, is quite different.

In contrast to Chastain’s photo, Morgan is presented up close; her body fills the entire frame. She is so close to us that it feels like we could reach out and touch her. She’s also in a passive, receptive pose, reclining on a tree branch. Her skin is glistening, but not with physical effort; it appears oiled, not sweaty. Her breasts are barely covered by her damp bikini top which is split in the cleavage area, as though it is about to come apart. Finally, she looks right through the barrel of the camera at the viewer, at us. The visual cues that the image gives us—the dazzling blue colour and the slight slit in her top, the sunlight hitting her glistening torso—draws our eye, tells us what to pay attention to.

In 1975, film critic Laura Mulvey coined the term “the male gaze.” This term describes the way audiences are aligned with the perspective of the camera in Hollywood cinema—a camera that is constructed from the social position of a heterosexual man, whose vision often lingers upon the erotically-presented bodies of women. The woman displayed within the male gaze is usually depicted as an object of desire for the characters within the story and for the (male) spectator, the audience. This visual dynamic reinforces a centuries-old power relationship where the man is the active agent—the one who looks—while the woman is the passive agent—the one who is looked at. Within Mulvey’s framework, the two images of Morgan and Chastain present the audience with two very different stories of women’s bodies.

The wider context of these two images matters in how we read them, too. After Chastain’s celebration photo swept around the world’s media, it was chosen as the cover of Newsweek and Time—brands whose reputations and profits do not primarily depend upon the sexualisation or objectification of women’s bodies.

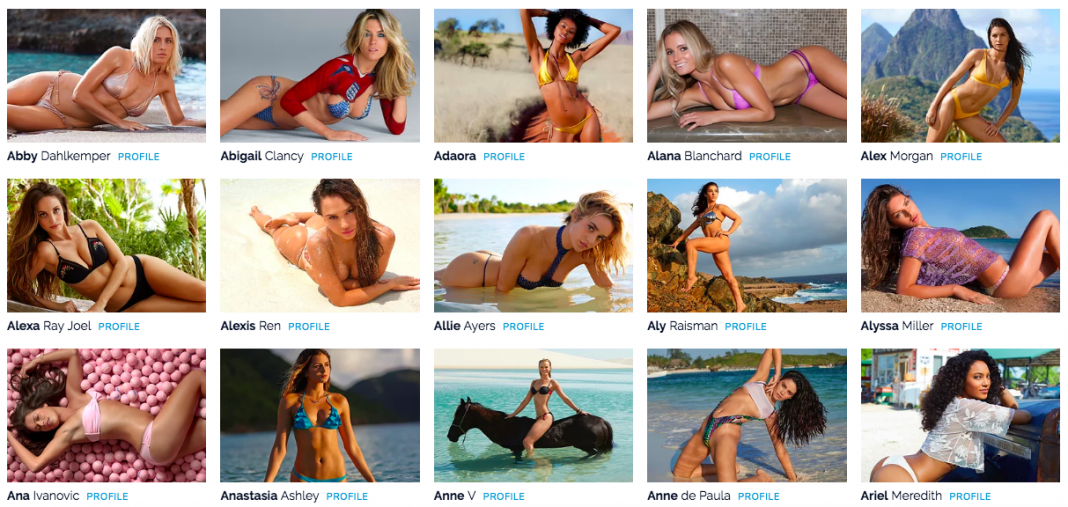

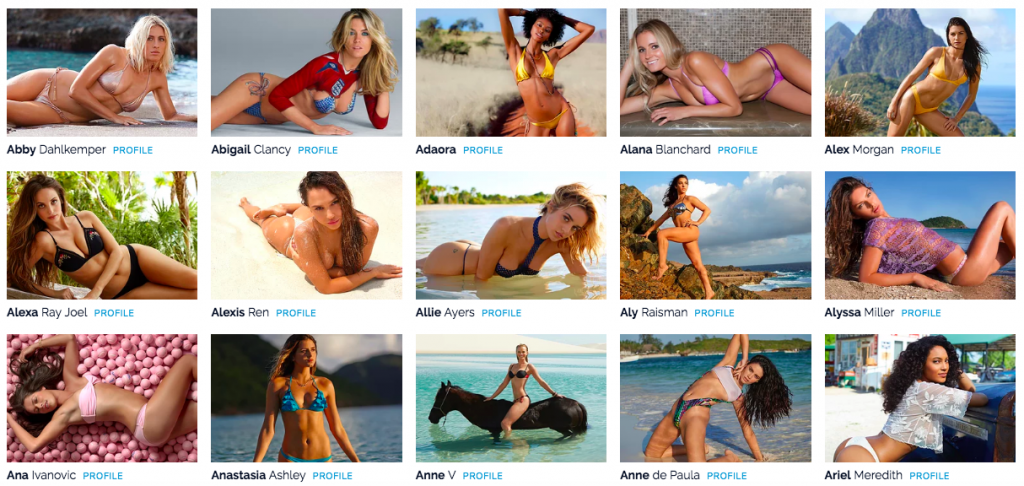

By contrast, and by way of example, the other two women on the alternative covers of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit 2019 are professional models. In fact, the vast majority of women on the SIS website are professional models—mostly white, cis, thin, and conventionally beautiful—posing provocatively in revealing swimsuits. This is SIS’s business model. Its profits depend upon the visual language of the male gaze.

If you didn’t know that Morgan and Dahlkemper were footballers, could you distinguish them from the rest of the models in the above screenshot? This question matters because there are wider contexts that factor into how we read images like these. What are the precise types of athletic bodies chosen for presentation in SIS? They’re the bodies of women who already fit the mould, who tick the boxes of the brand.

Women athletes have been fighting for generations to be seen as more than just sexual objects; to instead be taken seriously as competitors and to be judged on their work, not on how they look doing it. Former FIFA President Sepp Blatter’s suggestion in 2004 that women footballers should wear “tighter shorts” to promote the game is one infamous example.

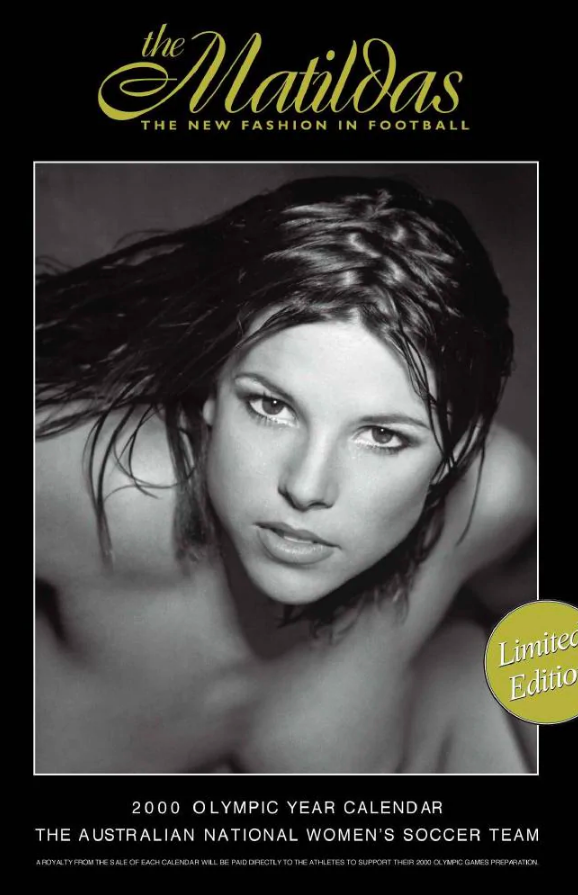

This fight reached a mini-crescendo in Australia when the Matildas famously resorted to creating a nude calendar in order to attract attention from potential sponsors in the lead-up to the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Salon.com wrote an article about the project titled “Full-frontal Aussie soccer babes,” which opens with the line “Even their fuzzy flesh down under is exposed in the Australian women’s soccer team calendar that will unveil 12 photos of pretty players in the buff.”

Look familiar?

Female nudity, or even female sexuality, is not the problem here. The crux of the issue is how women’s bodies are presented, whose bodies are chosen for presentation, why they’re presented in certain ways, for whom, and in what historical and cultural context. It’s important to think critically about these questions so that terms like “empowerment” don’t lose their radical political potential. In the context of feminism, empowerment means the liberation of all women from structures and systems of patriarchal oppression. This includes visual media.

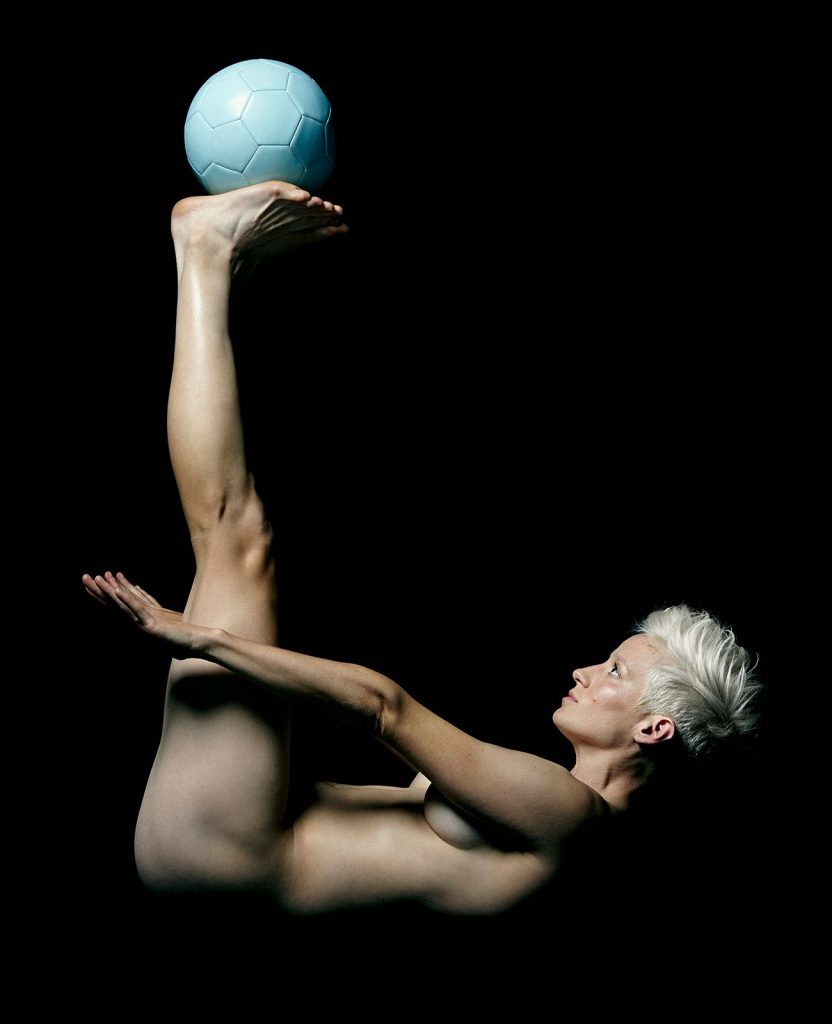

One outlet that creates a visual language of women’s bodies that contrasts with that of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit is ESPN’s annual The Body Issue. Like SIS, the models in The Body Issue are nude or semi-nude, and often photographed in natural environments. However, even the briefest of glances across The Body Issue’s archive demonstrates that these photographs approach the who, how, why, for whom, and context questions very differently.

ESPN is one of the best-known sports media outlets in the world. In The Body Issue, images of women athletes appear alongside their male colleagues. They are not traditionally colour-coded (in the sense that femininity is associated with light or pastel colours while masculinity is associated with darker or more ‘serious’ tones). Their poses, as well as their clothing (if they’re wearing any), do not artificially sexualise the athletes by drawing attention to particular body parts. Here is an approach to women’s bodies that is not constructed through the male gaze. In fact, The Body Issue features a whole range of non-normative bodies often made invisible by mainstream visual media, including the bodies of athletes who are not ‘slim’ and athletes who are differently-abled.

It is worth comparing images of the same athlete side-by-side in order to demonstrate the differences in their visual languages.

In this image of USWNT player Crystal Dunn for Sports Illustrated Swimsuit, much of the same visual codes of Alex Morgan’s cover are evident. Dunn is reclining on a beach. Her skin glistens with ocean water. Her hair is neat, swept behind her shoulders. One knee is bent while the other lies flat; a posture that recalls many European paintings of women reclining luxuriously on couches or beds. She looks into the camera, directly at the viewer, smiling slightly. Our eye is drawn to certain parts of Dunn’s body by virtue of her posture, the image’s composition (her body fills the entire frame), and also by its colour—the bright white bikini against her dark torso. All of these visual cues indicate that Dunn is passive, something to be looked at, and that we should look at certain parts of her.

Compare that with the photo of Dunn below for The Body Issue.

From her naturally frizzy hair to her leaping pose, this photo of Dunn is very different. It is dynamic. It’s a photo that demonstrates so many of the things that make Dunn a world class footballer: power, control, focus, speed. This photo has more in common with Chastain’s iconic image than Morgan’s in that neither athlete is paying attention to the viewer; they are fully absorbed in their own moment. Like Chastain, Dunn’s nakedness—rather than sexualising her—emphasises her athleticism. The rectangle of white that bends behind her, the dramatic lighting that casts those striking shadows on the far wall, and the streak of voluminous black hair signalling powerful forward movement, makes it seem as though Dunn is breaking through light itself. The composition of the image does not draw our eye to her sexualised body parts, but rather to her entire body as a force moving through space—as an athlete’s does.

In the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit article, Megan Rapinoe is asked about the male gaze that structures the magazine’s visual language. “There’s the assumption that everyone is posing for men, which I’m very much not, and I think probably the majority of women aren’t,” she said. “It’s OK to be sexy, it’s OK to wear a swimsuit, it’s OK to want to do that.”

It’s an odd moment considering the target market of the magazine, and an even odder one in an article that peppers images of USWNT players in revealing swimsuits amongst discussions of their fight for equal pay. Of course, nobody is saying that women athletes cannot or should not be, look, or feel sexy. And nobody is saying that athletes who pose for magazines like Sports Illustrated Swimsuit can’t feel empowered by their own images where they are depicted as hyper-feminine. People are complicated, and can have complicated or even irreconcilable desires; desires that even they may not fully understand. So it’s the job of those of us who consume the products of these desires to tease out their implications for ourselves and for others. Empowerment is a particularly slippery term in this sense because it can often conflate its feminist roots—as liberating women collectively through challenging patriarchal structures—with the individualist sense of feeling powerful within and through those same structures. Knowing the difference between them matters if we are to pursue gender equality faithfully.

The term “choice” is likewise tricky because it can easily confuse the power to conform to normative paradigms of gender or sexuality with the power to challenge those same paradigms. We live in a hyper-visual culture where what we see on screen or in magazines can affect the way we think about ourselves and our place in the world. As such, we must think critically about the words “choice” and “empowerment” when they’re used by athletes in these visual contexts: what choices are being made and by whom? Who is or is not empowered to make certain choices, and why? Do the choices these athletes make when presenting their bodies in certain ways challenge wider stereotypes or play into them? What impact do those individual choices have on collective cultural representations of women athletes or women more generally?

Empowerment and choices do not occur in a vacuum; the contexts in which these things take place fundamentally shape their expression. As feminist critic Rosalind C. Gill says, “[women] make choices… but they do not do so in conditions of their own making” (72). The visual languages used to communicate women’s bodies in sport are complex, tied up in profit-driven business models and target markets as much as social justice campaigns and pushes for diverse representation. These visual languages are textured with a cultural history that has constructed women athletes—and women more generally—largely as objects of male visual consumption. Much has been done the last decade to reclaim women’s individual power and agency from the invisible forces of capitalism and neoliberalism, but it is both irresponsible and naive to think that these forces do not continue to affect us—athletes and fans included.

It’s true that a picture is worth a thousand words, so next time a woman athlete poses for a magazine like Sports Illustrated Swimsuit and says they’re “empowered” because it’s their “choice,” we can all afford to pause and ask ourselves what those words really mean, and for whom.

References:

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Screen, vol. 16, issue 3 (1 October 1975), pp. 6–18

Rosalind C. Gill, “Critical Respect: The Difficulties and Dilemmas of Agency and ‘Choice’ Feminism: A Reply to Duits and van Zoonen” in European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 14, no. 1 (2007), pp. 69-80