This series, ‘Beyond The Matildas,’ takes us back through the history of Australia’s most-loved sporting team. It delves into the memories and experiences of its pioneers, and sheds light on the many aspects of life for Australia’s women footballers—both during and after their playing careers—that we don’t hear much about. ‘Beyond The Matildas’ celebrates the achievements of several generations of women players, while also looking at the more complex aspects of football for Australian women over time—the emotional struggles of losses and injuries, balancing football with other careers, the bumpy transitions into retirement, the new lives they forge, and the legacies they leave behind.

Brisbane—Queensland

It’s a sunny Sunday morning just like any other at the Southport Surf Life Saving Club on the Gold Coast.

Children in bright pink swimsuits and navy blue caps are sprinting across the beach and into the clear water, streaks of sunscreen painted across their noses. Tired parents cradling take-away coffees are cheering them on nearby; shoes off, toes wiggling in the warm sand. Hungry seagulls are landing in the shadow of the clubhouse, hoping for a discarded chip or two from the busy café inside. Two surf lifesavers stand in the shade of the watchtower, keeping an eye on the nippers hurdling the sparkling waves.

One of the two lifesavers is unusual, though.

She’s short—only 5’3”—with an unfussy crop of blonde hair salted firm around her ageing face. She has already done her warm-up laps in the nearby pool, as she does three times a week.

The beach-goers wander past and glance, impressed, but do not stop to say hello—though they should. This petite, unassuming figure is Sue Monteath, former captain of the Matildas, and one of the greatest women footballers Australia has ever seen.

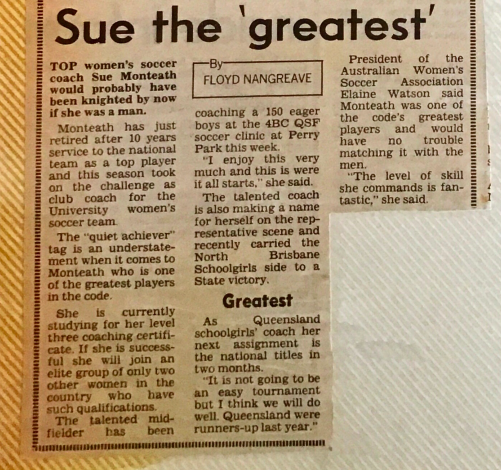

In a worn photo album in her house in Brisbane, amidst team shots and portraits of the former midfielder from her playing days, there’s a yellowed newspaper clipping; an interview from just after Sue’s official retirement in 1988. The article opens with the line, “Top women’s soccer coach Sue Monteath would probably have been knighted by now if she was a man.”

“That was a little bit extreme,” Sue said.

“But I always think back to the time when I taught at Ipswich Girls’ Grammar, in my early teaching career. At the same time there was a guy who was in the Australian Rugby team and he taught at the Ipswich Grammar School, the equivalent school for boys.

“When he needed to go away and tour with the rugby team, he was given all the time and on full pay, and yet when I went away with the Matildas, I had to ask for time off without pay… so that highlights the difference at that time.”

From kick-around kid to captain of the Matildas, Sue Monteath’s story is not just a story of a footballer.

Her story can be seen as a measure of the ways in which Australian culture has evolved in response to women who were willing and able to push its boundaries; to challenge, in their own small ways, the kinds of attitudes and traditions that were knitted into its social fabric.

Like a ripple of wind across the surface of an ocean, Sue—alongside many other early pioneers of Australian women’s football—was able to create the conditions for the thundering waves of today’s game.

“When I was in primary school, I actually got banned from playing soccer with the boys at lunch times,” Monteath said. “That was really frustrating. There was a female teacher that I had in year six and she thought it wasn’t ‘ladylike’ to be playing soccer, so she got me banned.”

But that didn’t stop her. Football was already in her blood, in her bones.

“I had three brothers and I played a lot of football in the backyard and fooled around and I didn’t have a problem [playing with them].

“Where I grew up, there was a grassy area behind our house and dad built a kick-board, so all of us would play endless hours of football in the backyard, making up teams of all the neighbourhood kids.”

It took less than two years from kicking a ball around in the backyard with her brothers as a senior in high school to being called up for the Matildas—a trajectory that seems almost unthinkable in today’s age of academies and professional pathways.

“I didn’t play [organised] football until I left school, even though I was playing all the time in the backyard.

“My brothers had played football and one of them had played some representative football, so I’d always been sitting on the sidelines wishing I could play.

“There was only an ‘open women’s team’ competition at the time in Brisbane; there weren’t really any youth teams or anything, so it seemed like a natural thing to go into then. That was in 1977. I was 17.

“I played for a club called Newmarket initially. I went through [one] season and they selected a state team, and then I got selected into the national team all in the one year.

“It was pretty meteoric.”

Monteath, or “Monty” to her team-mates, had a natural advantage in many ways. Not only did she grow up playing many different sports (softball, netball, swimming, athletics), which gave her confidence in her physicality and athleticism that many others her age lacked, but she also knew how to kick a ball properly, having practised on her own for so many years.

“People would come and start playing at 17 or 18, but they had no technique of just kicking the ball, let alone thinking about where to play the ball. I developed that at an early age.

“The coaches would use me as a demo sometimes, to show [other players] how to chip, or the different ways to approach the ball when you’re chipping or doing a pass kick or a lofted drive or whether you’re trying to hit with force at the goal.

“It’s nice to think that you can help other people get better, that’s for sure.”

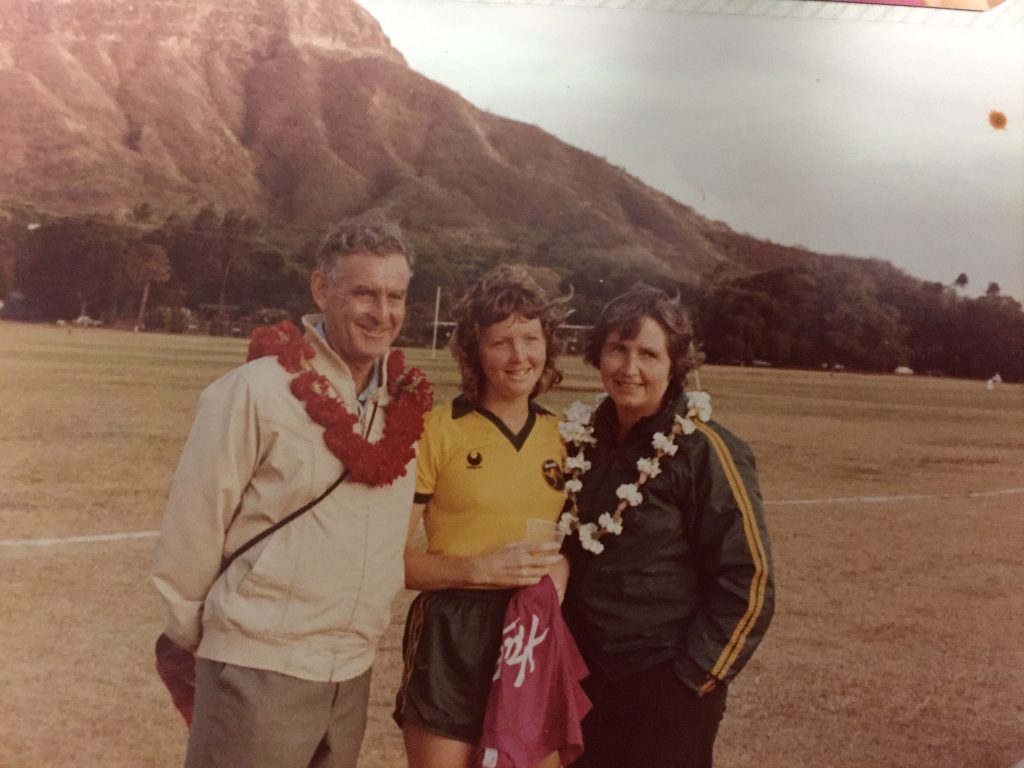

It also helped that both of Sue’s parents were supportive of her pursuit of football. In fact, they each became involved in the Matildas themselves during Monteath’s playing career: her mother, Jan, was the team physiotherapist while her father, David, was the team doctor.

“When we went to China, it was very helpful that we had Dad there because some of the girls were sick.”

“I got cut on the foot by a tag, so he had to actually stitch me up. I think he might have given me a local [anaesthetic] but it was really primitive; it was just sitting on the dresser in the room, we didn’t have proper [medicine].

“That was hilarious when we went there actually because [the Chinese hosts] gave us orange Fanta at half-time, and cups of tea. It was really weird.”

Football was not a career option for women in the 1970s and early 1980s, when Monteath was in her prime.

Like many of her team-mates, the midfielder studied and began a career in another industry altogether, knowing she needed to support herself while she pursued her passion for football. It was a constant balancing act.

“I did a degree and then did a teachers’ college degree. I remember we went to New Zealand and I missed four or five weeks from my teachers’ college, so I had to make an appointment to say how I’d make up [the time]—I think I did some extra time at school that I’d missed out on.

“I was very lucky in the school I taught at first that they’d give me time off without pay, which was very generous of them to a certain extent. That was good because there was one year, 1984, where I was away from school more than I was at school—we had a couple of tours that year.

“I don’t regret any of it, and I don’t think it significantly damaged my teaching; it was just grin and bear it.

“I basically planned for having time off and put money aside; that was just management.”

Having another career that provided financial support was crucial for the early Matildas, none of whom were ever compensated for their work. It seems a distant memory compared to the modern-day game, where many of the current Matildas are able to earn a yearly wage playing football, while many women’s leagues around the world continue to push towards professionalisation.

“We had to pay money, we had to take time off without pay, we didn’t get paid to play, and we didn’t have the support that is around today,” Sue said.

“I’m really enjoying seeing the American team at the moment trying to get equal pay. The surfing fraternity just awarded equal pay as well, so it’s just lovely to see that coming through.

“I still would have done everything I’ve done in the past regardless. I’m lucky that I had that opportunity and I hope I have contributed to more people playing the game.”

Her exit from the Matildas was about as unceremonious as you could get: in 1988, the Matildas brought in a new head coach who simply didn’t select her for an upcoming tournament.

“I’m not sure why that decision was made because I didn’t think that I wasn’t playing [well]; it was a strange decision to me.

“It’s sometimes hard to be objective about your own playing performance, so I figured they couldn’t take anything away from me. I was pretty disappointed at the time and people wanted to do big write-ups and say congratulations for all the work that you’ve done, and I just really went into my own shell and said ‘no, no, I’m just going to walk away.’

“I think for anyone it’s nice to give up on your own terms.

“Everyone has their disappointments and I guess, in some respects, it teaches you a bit of resilience.”

For someone who has played such an influential role in the development of women’s football in Australia, you would think that Sue Monteath would be a local legend. But she has countless stories of people—particularly her own high school students—who have no idea who she is, or who don’t recognise her contributions to the game.

“I joke around with my Year 12s because I was saying that I was going to watch the Matildas, and one of them asked ‘what’s a Matilda?’

“I gave her a serve and said, ‘Apryll, you don’t know what a Matilda is? There’s no hope for you!’ or something like that.

“Anyway, we left it at that, I didn’t say anything, and then she came back to me two days later and said ‘oh, miss, I found out what a Matilda was.’ And she’d gone and googled and found all these photos…

“I wasn’t going to say ‘well you should know that this is what’s happened and I played for the Matildas,’ I don’t turn around and do that, I just laugh. It was funny in the end that she went and found out about it.

“I don’t want to indicate that I’m superior because I’ve played for the Matildas; I’d never want to give that impression. It’s just something that I’ve been able to achieve and that’s really nice.”

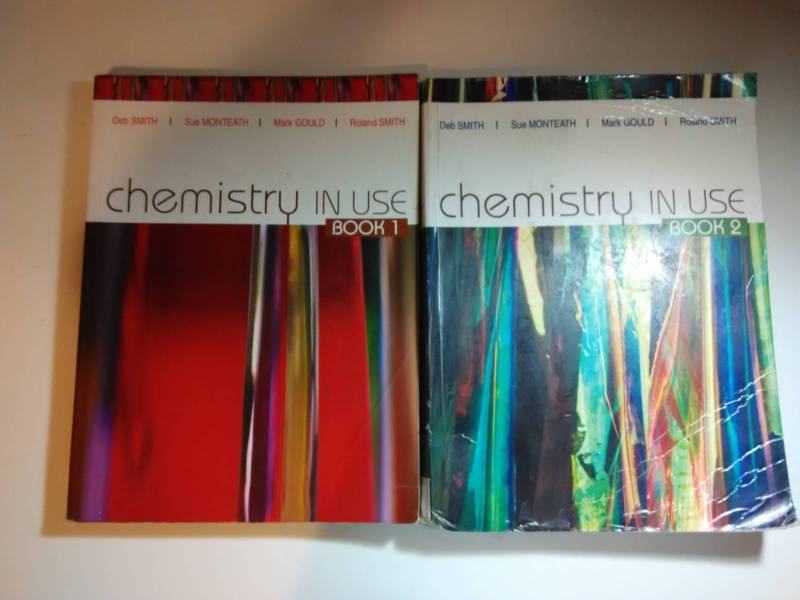

In fact, most of Sue’s students know her name for another reason: she’s the co-author of a high school science textbook, Chemistry In Use.

“The kids at my school know me more as an author of the chemistry textbook as opposed to a former Matilda… I don’t even say anything and the year elevens will go in and look at the textbook and go ‘oh, is that you?’ so that’s quite funny.

“Other teachers at my school know about me, and they’ll tell the kids before I say anything, and then the kids will come up to me. But I think everybody’s got their things they’ve achieved in the past… I value it personally more than wanting to publicise it to anyone.”

Her modesty belies the enormity of her achievements; not just in putting the Matildas on the world stage by captaining the side in some of their first ever international tournaments, including the Oceania Cup and the 1987 World Invitational Tournament—the precursor to the World Cup—but also in mentoring and coaching some of Australia’s greatest future players.

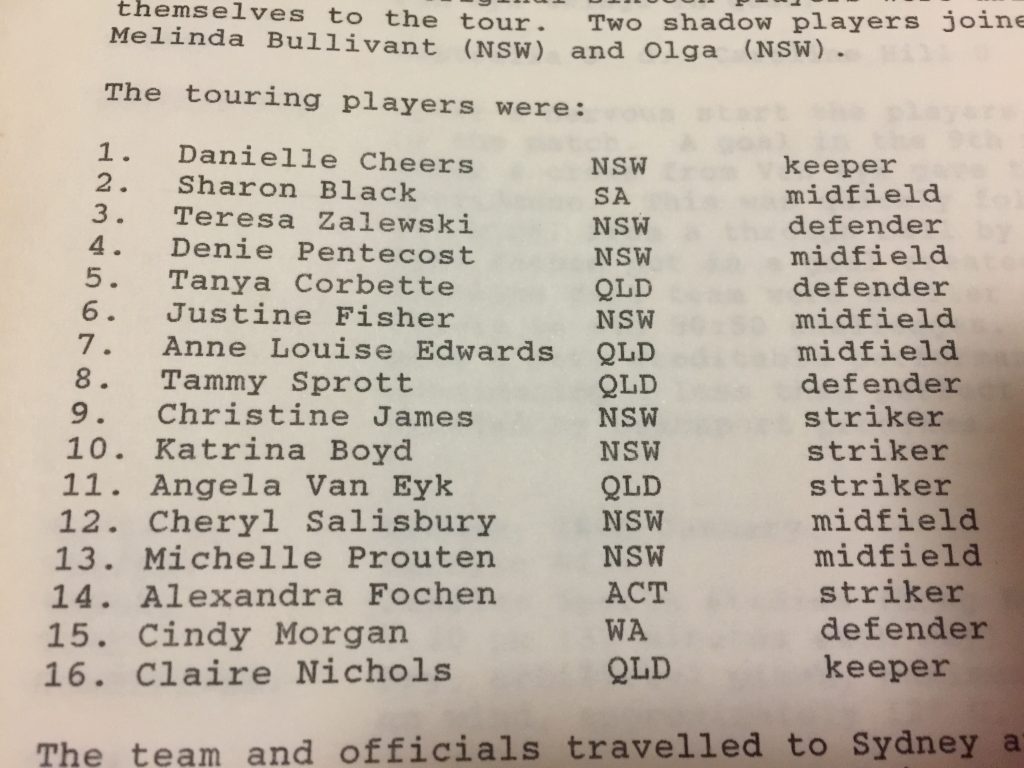

For example, Monteath was the head coach of the first Australian School Girls Team in 1989, going through the tournament undefeated. One of the sixteen players chosen for the tour of Hong Kong and China was future Matildas captain Cheryl Salisbury.

“That was fantastic, and it’s been nice to follow her career. She’s retired now also.

“You like to think that you’ve given them some exposure to the levels that they can play at and some idea of what you could do with your life. I think she played at the professional level which was coming in just as I was finishing.”

In the late 1980s, Sue was one of three women in Australia to complete her level C coaching certificate. She then went on to complete her B and A-levels.

“It was me, the only female, with a whole bunch of men. And even Steve Corica, the current coach of Sydney FC, he was in the squad that [we were given] and you had to coach them. I remember coaching him as a young player.

“It would have been nice to be with more women doing that. I’m grateful that they let me join but it didn’t make me feel like I wanted to go on and do more coaching, that’s for sure.”

Sue’s involvement in Australian football didn’t end when her Matildas career did. In fact, she continued to play club football with the University of Queensland until she was 52 years old.

“It didn’t have to be in front of a crowd of thousands. I just had a love of the game.

“They used to joke a lot about it when we’d play games, but it was all good; they were really kind. Often there’d be people who were 18 or 19 in the team, and I was like almost their grandmother’s age.

“It kept me young, if you like. It kept me engaged.”

Monteath had to give up playing entirely about eight years ago, when her knees began to give her trouble. However, the determination that saw her reach the heights of the Australian national team never left her, which is how she wound up being an active surf lifesaver on a Queensland beach at the age of 59.

“I really missed the team-work and that sort of thing, so I did my Bronze Medallion in the surf.

“I get the same kind of pleasures out of working with a team and occasionally performing rescue, so everyone pulls together and achieves their goal.

“The patrols are great; I learn lots in terms of First Aid and defibs and things like that.

“They’re people who are offering their time and doing it to give back, and I really like that quality about it.”

Giving back to the community is an ongoing theme throughout Sue’s career—from helping her team-mates to learn the right techniques of kicking a ball through to her work as a high school science teacher, her surf lifesaving, and her regular volunteering at various sporting events around the country, including the Commonwealth Games, the Olympics, and the Paralympics.

I asked Sue how she feels about her own legacy; about her status as a pioneer of the women’s game in Australia. She was predictably humble, but also conscious—with the benefit of hindsight—of the important role she has played.

“I’d like to think I have had an influence on young girls playing football, both in terms of the profile and in terms of being a Matilda. Also [through] the coaching of the school girls and just being out there [playing].

“I was promoting the fact that women could play football as well as men could.

“It’s funny how people come up to you and say they remember you playing. Sometimes I guess you’re not aware of what influence you might have.

“I’m no longer playing so I’ve been able to put it in perspective. I wouldn’t like to downgrade it and say it was just a chapter in my life; it’s still a really big thing and I love that I was able to do it and share so many memories.

“I was lucky because I was given the opportunity and I grasped it with both hands. I have absolutely no regrets. I hope I have contributed to more people playing the game.”

The boys and girls of Southport Surf Lifesaving Club complete their swim circuits in the cool, clear water, indistinguishable in their pink vests and dark blue caps. Not far from edge of the water, Sue Monteath stands guard in the shade of the watchtower, her bright eyes scanning the tumbling waves.