“Nobody cares about women’s football.”

From old fans, new fans, and commercial brands, the reply to this is an increasingly loud “we do!”

At times, it feels like women’s football is on the edge of something truly special; that it has never been more popular. Yet it is often forgotten that in the early days of the women’s game, plenty of people cared.

The history of women’s football is a long one filled with pre-dawn rises and dashed hopes. In Europe, the first reported women’s football matches go back to the 1800s with the game taking off in early 1900s Britain. Spectators flocked to see Dick, Kerr Ladies and St. Helen’s play out a match in front of 53,000 people at Goodison Park, Liverpool.

In Australia, on 24 September 1921, 10,000 people went to watch North Brisbane take on South Brisbane at the first public match of women’s football at the Brisbane Cricket Ground. Weeks later, down in Ipswich, another 3,000 turned up for a second women’s football match.

A lot of people cared about women’s football. That was the problem.

In 1921, the English Football Association banned women from playing on Association members’ grounds. The ban resonated around the world with many other football associations instituting their own bans, including Australia in 1922. France followed in 1932 while Germany refused to permit women into the association at all.

While the ban was in effect, women’s football essentially went underground until the English FA lifted its ban in 1971. Once again, most of the world followed England’s example.

Women’s football was back. But it had 50 years of catching up to do.

Can’t start a fire without a spark

From the early 1970s to the early 1990s, efforts to bring the game up to speed were slow. While official bans had been lifted, shadow bans persisted with women’s clubs and leagues around the world often left with little to no support.

Locked out by their male counterparts, many nations started their own women’s football associations – English Women’s FA (1969) and Australian Women’s Soccer Association (1974) are just two examples.

With the initiation of the FIFA Women’s World Cup in 1991 came the first sparks of true growth. Football ignited in countries like the United States, Sweden, Norway and China.

The 2000s saw many more nations start to take the game seriously. In Australia, AWSA was disbanded and in 2005 the women’s program came under the newly formed Football Federation Australia. After the 2007 FIFA Women’s World Cup in China, a quarter final run by the Matildas saw a double-digit explosion of girls playing the game.

In France, the creation of a training centre for women at Clairfontaine by the France Football Federation started to pay dividends with a participation boom following the 2011 Women’s World Cup.

The contagion slowly spread – the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria – then ignited – England, Spain, Italy and now the Americas with Chile, Mexico, Colombia and Argentina.

No longer dancing in the dark

In many spheres of public life and discourse, necessary lamentations occur over the power afforded to gatekeepers – the large institutions (and the individuals that run them) that set up and shape the agenda.

While this set-up can hold back some of the more divisive ideologies infecting our current public dialogue, it can also close the door on many communities outside of the mainstream.

The mid to late-2000s changed that for the media landscape. The internet and accessibility of digital media allowed for independent media to grow. In women’s football, media organisations proliferated; She Kicks going online, The Women’s Game (2008), Women’s Soccer United (2008) Equalizer Soccer (2009), Pitchside Report (2011), Foot d’Elles (2012), Our Game Magazine (2012), and many more.

Suddenly, the gatekeepers were no longer required for supporters of the game to obtain information on women’s football. If those in charge didn’t care but you did, you could search out information from trusted sources.

It was in that same time period that social media became more widespread with Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube all enjoying extraordinary growth.

It’s no coincidence that the outbreak of women’s football can be traced back to Patient Zero: the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup. It was the first real social and digital media women’s football tournament in history.

New Tweets per second records! End of the #WWC final: 7196 TPS. And today's end to the Paraguay/Brazil game is now 2nd with 7166 TPS.

— Twitter (@Twitter) July 18, 2011

Alongside new independent sources, the broadcasting of news and results was made easier thanks to social media. A tweet about a W-League match could be sent in Australia and seen in North America or Europe.

Not only that, but now the players could get in on the action as well. They could tell their own stories; they could make their voices heard.

Players could start conversations about issues that mattered to them, whether it was the playing surface at the 2015 Women’s World Cup, Vero Boquete’s campaign for women’s representation in FIFA games or, more recently, players speaking out about inequity, sexual harassment or abuse within their programs.

He creado una petición en http://t.co/DdP7p9N3 para que EA Sports incluya mujeres en el FIFA. Me ayudas?? https://t.co/Wz0ifv1W

— Verónica Boquete (@VeroBoquete) February 20, 2013

Women's National Teams are #INTHEGAME #FIFA16! https://t.co/WIBB9Z7hc3 More: http://t.co/9yKSz4tRtK

— EA SPORTS FIFA (@EASPORTSFIFA) May 28, 2015

For supporters, the early days of tweets (remember the frantic refreshing, anyone?) and status updates evolved to include live streams, vlogs and gifs.

This accessibility has allowed for greater visibility of women’s football at any time of the day.

Waking up in the morning you can find highlights and gifs from a plethora of leagues and matches around the world. Great goals, top saves, world class skills on display at the tap of your mobile phone. It’s still not enough (we are greedy like that) but it is more than we – or the game – have ever had before.

Social media has provided a powerful microphone for women’s football, with federations and companies finally listening.

Message keeps getting clearer

It was a spectacle like no other: 28 of the world’s best footballers were flown to the French capital. The show was not dissimilar to an extravaganza at Paris Fashion Week when, finally, the World Cup kits were unveiled.

For the first time, the world’s biggest sportswear brand, Nike, had produced dedicated kits for women’s national teams to wear at the world’s biggest women’s sporting event.

On the same day, Nike reaffirmed its commitment to women’s football with a three-year deal to become official partner of UEFA Women’s Football, as well as the match ball supplier for UEFA Women’s competitions, including the Women’s Champions League and the Women’s Euro 2021.

https://twitter.com/UEFAWomensEURO/status/1105139869196734470

“We believe this summer can be another turning point for the growth of women’s football,” said NIKE, Inc. Chairman, President and CEO Mark Parker.

“And our bigger ambition is for that energy and participation to extend into all sports. Nike’s commitment is to continue our leading support of competitive athletes, invest in the next generation at the grassroots level and deliver more innovative and compelling product design for women.”

Days before, Nike competitor Adidas also released World Cup kits for its six nations and announced that Adidas-sponsored players on the winning World Cup team would receive the same performance bonus payments as their male counterparts.

“We believe in inspiring and enabling the next generation of female athletes, creators and leaders through breaking barriers,” Adidas’ head of global brands Eric Liedtke said.

Equal pay for equal play.

.#WWC #WorldCup pic.twitter.com/Btt3lTfYAG— adidas Football (@adidasfootball) March 8, 2019

Then, just this week, the English FA announced a £10m deal with Barclays Bank – the largest corporate investment in UK women’s sport – to sponsor the Women’s Super League for three years starting in 2020.

The sponsorship will also support the FA Girls’ Football Schools Partnerships to improve access to football for girls in schools.

All of this news was met with much public fanfare and positive sentiment for the brands, as well as some “about time” sentimentality.

But it is not just altruism driving these investments. Women’s football is starting to sell.

The US Women’s National Team has regularly sold out stadiums at home, and their giant fanbase pulls in considerable revenue for the United States Soccer Federation. On social media they are a behemoth with a combined 4.5 million followers on Instagram and Twitter alone.

But they are not the only ones producing notable dollars. France, England, Sweden, the Netherlands, Australia – all their national teams have witnessed sell-out games in the past 18 to 24 months.

23,750 tickets for the Netherlands v Switzerland @FIFAWWC play-off 1st leg in Utrecht sold out in 25 minutes – assuming everyone turns up, will set a new record for a @UEFA Women's World Cup or @UEFAWomensEURO play-off. https://t.co/MwAbAGHtQq

— Paul Saffer (@UEFAcomPaulS) October 19, 2018

https://twitter.com/UEFAcomPaulS/status/1048309563810832384

games sold out in america, england, wales, scotland, the netherlands and france. women’s football is really becoming a global success i’m so happy. pic.twitter.com/zK7nuBMebV

— Autumn (@wntbronze) November 10, 2018

At league level, there has also been a significant uptick in attendances across the globe. Many women’s leagues are now seeing record average attendances including Mexico, Spain and England.

In fact, 6 of the top 8 record club attendances have been in past 15 months.

https://twitter.com/BBCSport/status/993087983027879938

¡¡ Seguimos haciendo historia !! 👏👏👏👏

El Estadio BBVA Bancomer recibió a 51,211 aficionados para superar, una vez más, el récord de asistencia en un partido de clubes de Futbol Femenil.

Muchas gracias por ser parte de este momento #VamosPorEllas #FinalRegiaFemenil ⚽️👧 pic.twitter.com/wr9al4f9Lu— LigaBBVAFemenil (@LigaBBVAFemenil) May 5, 2018

🙌 ¡HISTORIA! 🙌

🙌 ¡HISTORIA! 🙌

🙌 ¡HISTORIA! 🙌🏟 ¡ 60.739 espectadores en el Wanda @Metropolitano para ver el #AtletiBarça! 💥

🔝 ¡Récord mundial de asistencia a un partido femenino de clubes! 😍🤩#HablamosDeLoMismo#LigaIberdrola pic.twitter.com/TcUXqsfV6O

— LALIGA (@LaLiga) March 17, 2019

And you can’t miss the excitement on social media.

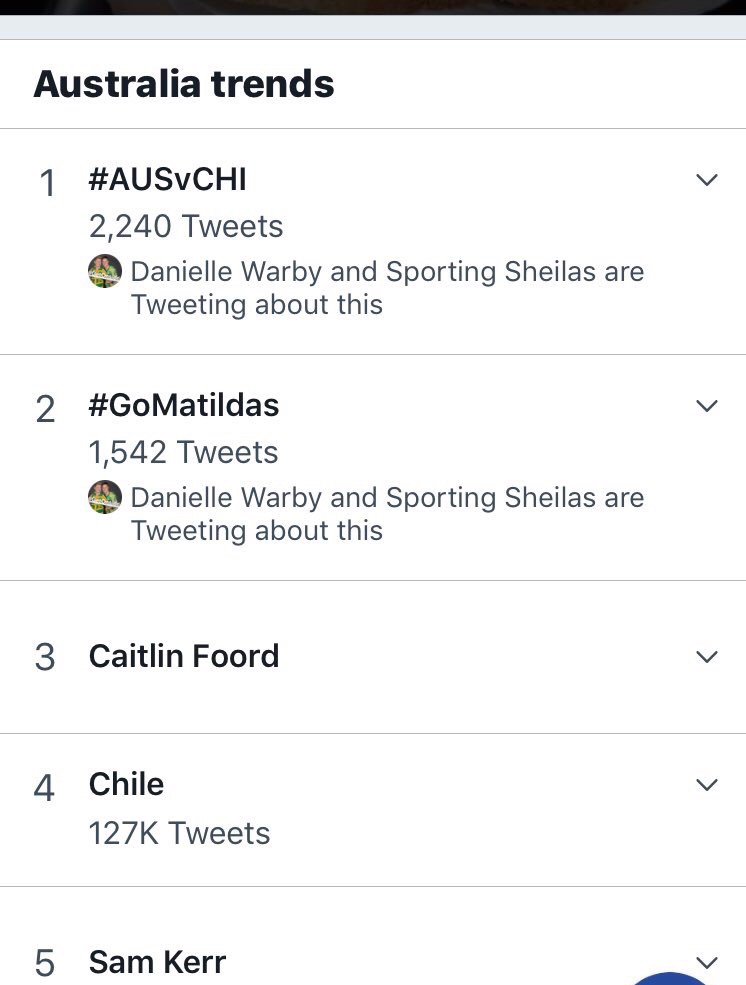

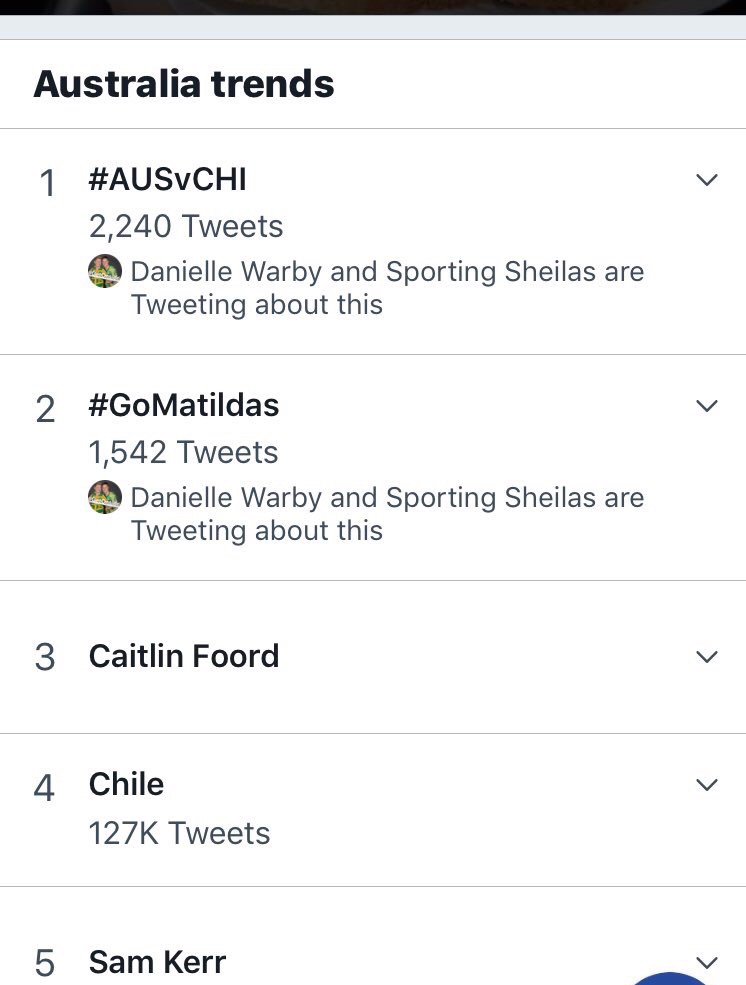

Hit up Twitter on pretty much any Matildas match day now and the top trends in Australia are the match hashtag (#GoMatildas) or a particular players’ name after a standout performance.

In Spain, the #AtletiBarca game was full of colour, noise and excitement rapidly shared across the globe. History was being made and you could be a part of it in real time – no matter where you were.

Atmosphere's great at #AtletiBarça. pic.twitter.com/LI9gyc1tpo

— Bea (@Iniyi) March 17, 2019

Este momento HISTÓRICO. VIVIRLO. Es IMPARABLE!! Apuesten por el futbol femenino, está aquí para quedarse y esto es solo el principio. Lleno absoluto en el #wandametropolitano para ver el #AtletiBarça @LigaIberdrola #futfem pic.twitter.com/ZQ4z3dWZwb

— Sonia (@sonyeta) March 17, 2019

60.739#AtletiBarça#LigaIberdrola pic.twitter.com/oKJ038XPLP

— Sandra S. Riquelme (@sandisup) March 17, 2019

These strides are becoming more visible, and it appears to be spurring others on. And why not? In many nations around the world, women are the majority of the population and/or key decision makers for families or in their own individual lives.

Women’s football is no longer just corporate social responsibility – it’s becoming profitable.

There is also a palpable shift in the way federations invest in and market women’s football. Players’ online visibility means they can now call out the decision-makers in footballing organisations and demand better treatment and support.

That public accountability is forcing change to occur. Colombia’s women’s footballers, for example, were able to create enough noise and garner support to result in the backpedalling of plans to cancel the professional league.

https://twitter.com/MelissaMOrtiz/status/1105611431486078977

A commission is now being created to look for investment and make it more financially stable.

After weeks of national team players speaking out about their treatment at the top level, the Argentine Football Association pledged to start a new professional league in June, provide more resourcing and create a high performance centre for the women’s game.

“This association has one promise, to improve football,” AFA president Claudio Tapia said. “We are going to keep working to develop women’s football in all provinces.”

And earlier this year, although without as much controversy leading up to it, the Chinese Football Association announced its new professional league entry regulations require all their men’s Chinese Super League teams to have equivalent women’s teams by 2020.

CFA acting president Du Zhaocai told FIFA.com:

“We have noticed that quite a few of the world’s most successful clubs have women’s teams as well and boosted by successes of the men’s teams, their women’s teams have developed fast and achieved tremendous successes too.”

But some are still not convinced.

https://twitter.com/AlexiLalas/status/1105523503464243201

There is a special kind of financial amnesia that comes with such comments.

For profitability to happen, there needs to be investment. Sometimes that investment must be substantial. Most of the major men’s leagues around the world ran at significant losses in the early days of their operation, and many professional men’s clubs still do.

And yet, to many, pouring money in men’s football is an ‘investment,’ but putting money into women’s football is a ‘loss.’ Luckily, happily, that spark is creating a fire, and this women’s football revolution is being tweeted, videoed, snapchatted, livestreamed and Instastoried.

Scrolling gingerly down any social media post, you will still occasionally see a variation of a theme: “Nobody cares about women’s football,” they shout into the void.

Except now we very much do.

RESOURCES

Tate, Tim. Girls with balls – the secret history of womens football, John Blake Publishing Ltd, 2016. Available at https://www.amazon.co.uk/Girls-Balls-Secret-History-Football/dp/1782194290

Dick, Kerr Ladies FC. (2018). History of Women’s Football. Retrieved from http://www.dickkerrladies.com/

with the ball at HER feet. (2018). Brisbane Women’s Football History Retrieved from https://www.withtheballatherfeet.com.au/index.html